In honor of President’s Day, I present a question: Does art peddle in alternative facts? Let's consider what is arguably the most famous history painting of the Revolutionary War, perhaps in all of American history: Washington Crossing the Delaware. Our soon-to-be first president, George Washington, and his men are depicted in valiant and heroic poses on a monumental canvas that has pride of place in the heart of the American wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Trivia: A version also once hung in the West wing of the White House. Our president, Donald Trump, out to kill the National Endowment for the Arts, would have seen it en route to his office every day). But, is the painting to be trusted? Let’s start with what it gets right. The facts. The surprise crossing did happen -- on the night between Christmas and Dec. 26, 1776. And Washington was victorious once on land, his troops nimbly defeating Hessian mercenaries fighting for the British at the Battle of Trenton. Fatalities were relatively few, with three Americans dead and six wounded. Twenty-two Hessians lost lives. But the 1851 painting takes a number of liberties, which in this case were intended to motivate European reformers with the example of America’s revolution on the heels of 1848 worker uprisings. (Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto was published that February in London, and the world was a’twitter with talk of class struggles). What does artist Emanuel Leutze do to make war in the dead of winter look heroic and winnable? First, he creates a stable triangular composition anchored by the planful and stoic Washington. The sun is breaking, bathing faces of several boatmen in a gentle and optimistic light. Washington is clad in spotless military uniform. And the lead boat is followed by an array of support vessels in formation behind their indefatigable leader. But, truth be told, that’s actually not how the crossing went down. At all! Consider these “alternative facts” in the painting:

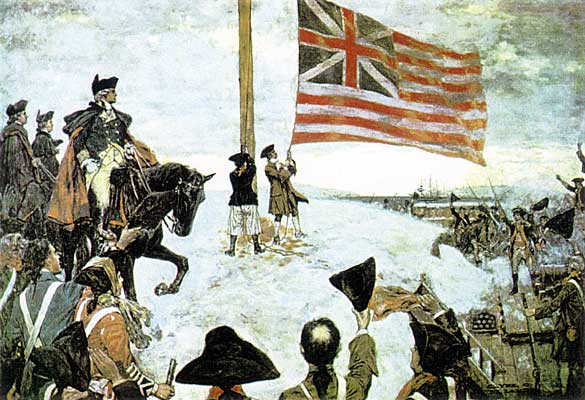

The Raising of the Grand Union Flag in 1776 in Somerville, Massachusetts. Clyde O'DeLand.

Actors taking their places in a Durham boat to re-create Washington's crossing

The Rhine at left; the Delaware River at right.

So, can we accept Leutze’s picture, with its myriad artistic liberties? I say yes. Absolutely. Leutze has the fundamental facts straight, and his painting, crafted some 75 years after the event it depicts, does not deign, and never professed, to be “news.” Art cannot be fake news because art is “fake” to begin with, and the audience for art understands and expects myth, fancy, illusion and distortion. We expect news, though (and our presidents), to be truthful -- something far more elusive, compelling, and beautiful than the real world.

2 Comments

Luscious back sides, liquid gold and alluring goddesses: Four must-see paintings for a sexy Valentine’s visit to NYC museums! Looking for a little romantic inspiration this Valentine’s Day? Look no further than NYC’s great art museums. Here are four surprisingly sexy stops to schedule. The Brooklyn Museum is showing off the massive photo-realistic paintings of Marilyn Minter, the provocateur who debuted 40 years ago but has really turned on her wild side in the last 10. Open mouths drip liquid gold and red lips puff silver beads into the air. Try this one on for size (it fills a wall). Pop Rocks, Marilyn Minter, 2009, at the Brooklyn Museum through April 2. Pierre-Auguste Cot, the little-known French artist, found a sly way in 1880 to show young love -- and perky nipples peeking out from a diaphanous gown. He created the illusion that the young couple are drawn from a myth. Back in the 19th century (and before), the only safe way for an artist to exhibit such titillating images was to pretend the subject came from great literature. Enjoy The Storm at the Met in Gallery 827 near the Impressionists. The Storm, Pierre-Auguste Cot, 1880, The Metropolitan Museum of Art A divine derriere is on view just a few galleries away in Titian’s Venus and Adonis. Knowing her lover is about to perish in a hunt, Venus tries to restrain the handsome hunter and prevent him from flying the coop. But Adonis will have none of it. (With insouciant indifference to the goddess’s charms and her warnings of danger, Adonis hunted a wild boar and was gored to death). The great Tiziano was surely only too aware that viewers would stick with the image longer if he offered some skin. So we also get an alluring view of Venus’s luscious backside. And Adonis offers a nice chest view, too. Venus and Adonis, Titian, c. 1540, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gallery 607 As for Venus’s front side, look no further than Peter Paul Rubens. He’s also enamored of the Venus and Adonis hunting myth -- in a painting that would have been perfect for the walls of a Baroque-era country hunting lodge, where weekend hunts occupied noblemen indoors and out. Wild hair and a highly precarious posture only add to Venus’s allure, as her voluptuous figure is right there for the taking in the Met’s second-floor galleries. Venus and Adonis, Peter Paul Rubens, 1630s, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gallery 628. For a private tour of these paintings, or any other subject on your list, check out Heart of the Art! Or find us on Facebook.

Contact: [email protected] or 718-644-5789 |

About EmilyWhen I'm not teaching art history or touring, I'm scouring the city's museums for art tidbits to share with you. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed